Project 1: Depicting the Real

Reality has many facets. It is almost a self-evident truth in the world of arts, as each artist can choose to depict the same object from his or her unique viewpoint. Less appreciated is the fact that a scientific image also represents an aspect of the object that interests the investigator, rather than what the object “really looks like.”

Scientific Illustrations: the neuromuscular circuit

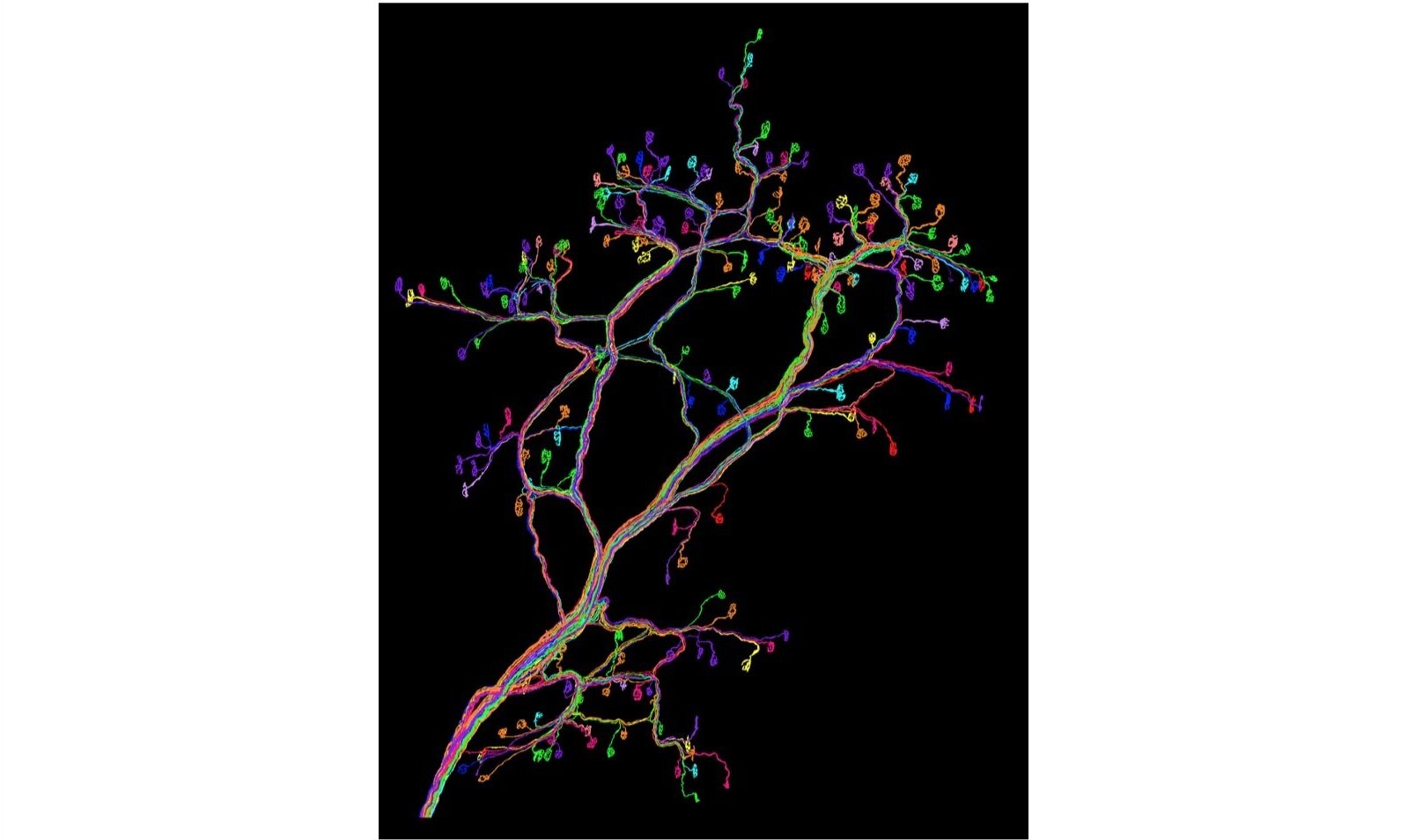

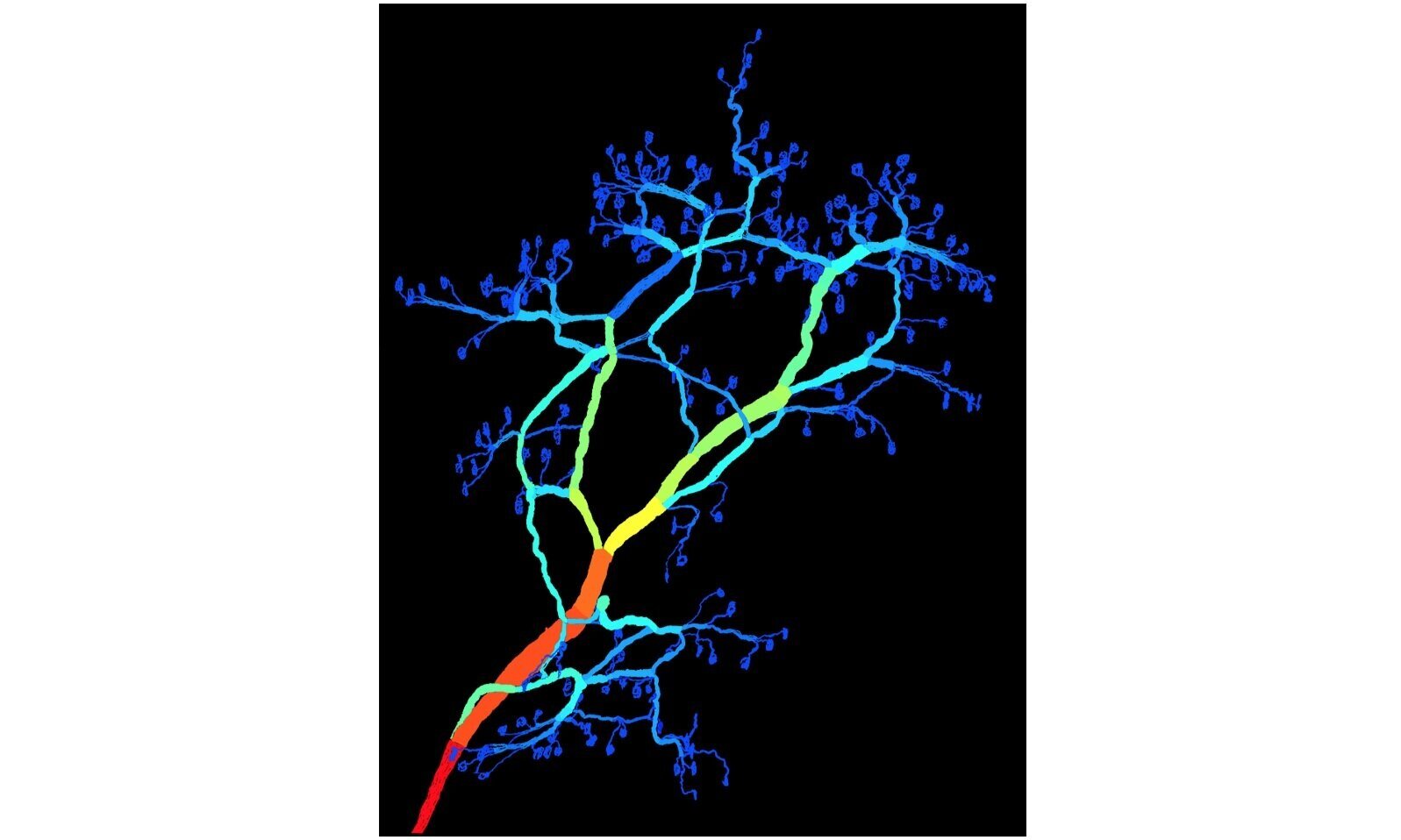

Here are three images of the same object: the processes of all nerve cells (“neurons”) that project into, and form contacts with, a small muscle. These neurons are filled with a yellow fluorescent protein, so they are visible under a fluorescent microscope. Each of these neurons sends out a long process called the axon, which is the output cable of the neuron to convey electrical signals to its targets. Once it reaches the target muscle, the axon branches out like a tree. The flower-like structure at the end of each twig is the contact with a single muscle fiber, called the neuromuscular junction, through which the neuron commands the contraction of the muscle fiber. In the adult muscle, each neuron controls numerous muscle fibers, but each muscle fiber receives input from only one neuron.

Image 1 is close to what this neuromuscular circuit appears to the naked eye under the fluorescent microscope – a collection of glowing spaghetti. But even this image omits many elements, such as the muscle fibers and other types of cells surrounding the junctions: we chose to label only the neurons.

Image 2 is the outcome of laborious image analysis. Each neuron is rendered in a distinct color, so its branches are visually disentangled from those of other neurons. Now we can easily tell which neuron controls which muscle fiber – the circuit diagram is revealed.

Image 3 highlights the collective behavior of axons. Imagine that the nerve bundle is a river, which branches out into smaller and smaller tributaries (branches of axons) until each terminates in a reservoir (neuromuscular junction). Imagine also that the water volume in each tributary is proportional to the number of terminal reservoirs it supplies. The colors represent the water volume in each segment of the tributaries. In other words, a reddish color means more neuromuscular junctions downstream of the segment.

Which of the three images is “true”? None, as each emphasizes one aspect of the neural circuit at the cost of others; all, as each is a faithful representation of the things we chose to focus on.

Ref: Adapted from Lu J et al. (2009) The Interscutularis Muscle Connectome. PLoS Biology 7(2): e1000032. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000032

Artworks: Still life

The three still life paintings are executed by different artists throughout three distinct periods of art history. Although they depict similar objects (lemon, pitcher, dish-ware), the choice of artistic focus and techniques differ dramatically. As seen in these three chronological images, representation becomes more and more abstracted as the timeline of canonical art history progresses. Does this mean any one image is more or less ‘real’ than the other? Some might argue yes, some might argue quite the opposite. Through highlighting techniques like color, light, form, and spatial relationship, the artists are presenting the same objects to the viewer in different ways, evoking specific but varied aesthetic and emotional responses.

Artwork 1: A member of the Dutch Golden Age, Willem Kalf was one of the great still-life painters of the seventeenth century. True to Kalf’s style, this image intentionally portrays rare objects that appealed to the wealthy Dutch class, organized very precisely against a dark background. Kalf uses light, sheen, and rich textures to convey the luxury of the objects to the viewer. Despite the hyper-realistic painting style, the intentionally staged scene is in a sense, a false representation of reality.

Artwork 2: Henri Matisse, known as the greatest colorist of the 20th century, used color, outline, and flattened forms to depict a scene on a canvas. Matisse used intentional relationship between form, space, and color to make objects appear both at once floating in space and situated realistically in the pictorial plane. Here, Matisse uses muted colors to show highlights and lowlights, and to ultimately bring the scene to life.

Artwork 3: Roy Lichtenstein, considered one of the most seminal American pop artists, references the techniques of the Cubists in this hybrid piece. Cubists (most notably Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque) were interested in depicting the “real,” but not in the traditional style of previous eras. Historically, artists used optical illusions like linear perspective, single vanishing points, and shading to turn the two-dimensional plane into a three-dimensional scene. Cubists rejected the idea that art had to precisely mimic nature. Cubists, instead, used fractured and geometric shapes and multiple vanishing points to emphasize the two-dimensional nature of the canvas, but suggest the three-dimensional quality of objects.