Scientific images usually have a clear distinction between the object of interest and the background. Classical painting adopts a similar perspective between the foreground and the background. However, such distinctions are in a sense artificial, as they depend on where the viewer’s attention is accorded. The illustrations given below abandon this dichotomy; instead they leverage and emphasize the symmetry and complementarity between the “foreground” and the“background”, as the Yin and Yang in Taoist philosophy.

Science Work

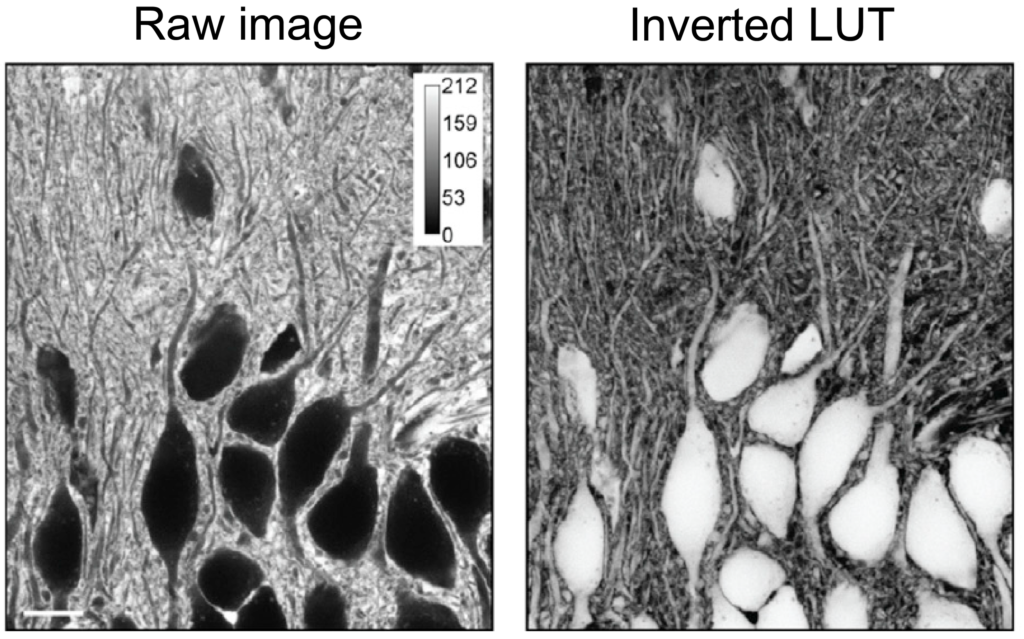

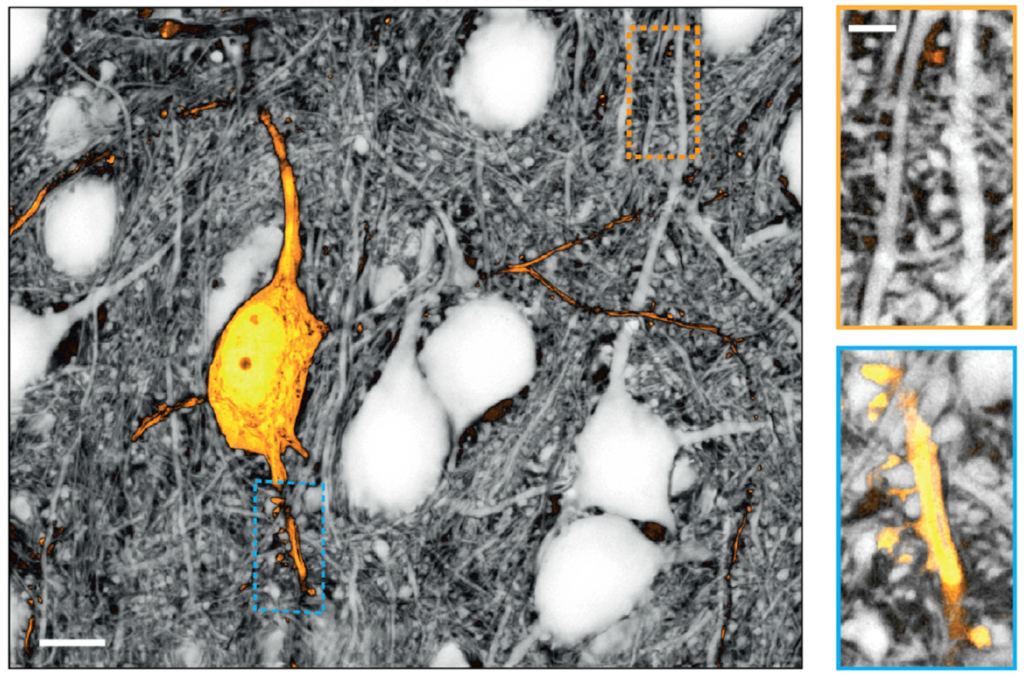

The brain is packed with nerve cells. Each nerve cell has many extricate processes that may be very thin and highly tortuous. Together, this dense network of subcellular structures surpasses the resolving power of conventional optical microscopes. Moreover, all cells in the brain are surrounded by extracellular space (ECS), an exquisite labyrinth filled with fluid. The caliber of “tunnels” and “canals” of ECS also falls below the resolution limit of conventional optical microscopes. To observe the nanoscale organization of the neuronal network or, conversely, that of the ECS, Dr. U. Valentin Nägerl and colleagues devised SUSHI (super-resolution shadow imaging), which cleverly uses negative images. They perfuse the ECS with a fluorescently labeled fluid and imaged it with STED microscopy (a Nobel prize-winning super-resolution technique developed by Dr. Stefan Hell). The cell bodies and processes, unlabeled by the fluorescent dye, become dark voids in the image. Therefore, inverting the Lookup Table (LUT) of the raw image yields a clear image of the cellular structures (Figure 1). Moreover, if a cell is labeled with a fluorescent molecule of a distinct color, the superimposed positive image of the cell (yellow) and the inverted image of ECS (gray) together give the spatial organization of processes of cells that contact it, either sending or receiving information from it (Figure 2).

Ref: Jan Tønnesen et al., Super-resolution imaging of the extracellular space in living brain tissue. Cell 172: 1108-1121, 2018.

Artwork

Traditionally, visual artists portray important objects in the foreground, relegating less important ones to the background. The contrast between the two naturally directs the viewer’s attention to the intended focal subject.

However, in Untitled (Stairs) (Figure 1), the artist Rachel Whiteread swaps the concreteness of a familiar object with the emptiness that we normally associate with non-being, by creating a monumental plaster cast of the space surrounding a staircase. As stated by The Tate Modern’s description:

“Whiteread’s casting process has transformed the stairs into an abstracted geometric composition which combines physical familiarity with a mental conundrum – that of trying to envisage the original structure from which the new object has been derived.”

Traditional Chinese landscape painting makes clever use of blank space (Figure 2). Intentionally left on the paper, the blankness may represent the sky, the river, rolling fields, etc. and thus acquires a concrete meaning in the context. The calculated arrangement of “foreground” objects in the painting cues the viewer to substantiate the blank space with his or her own imagination.

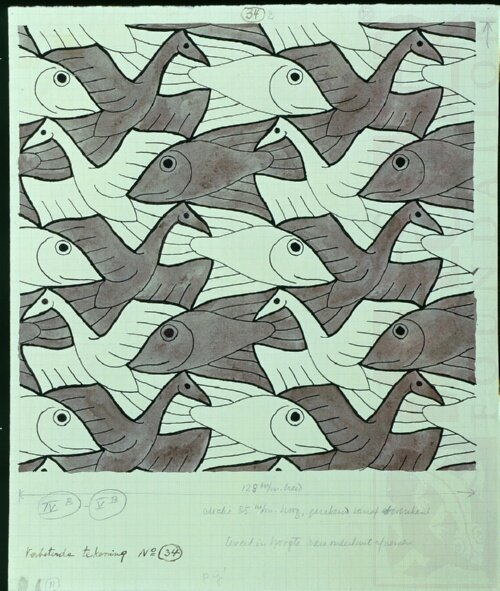

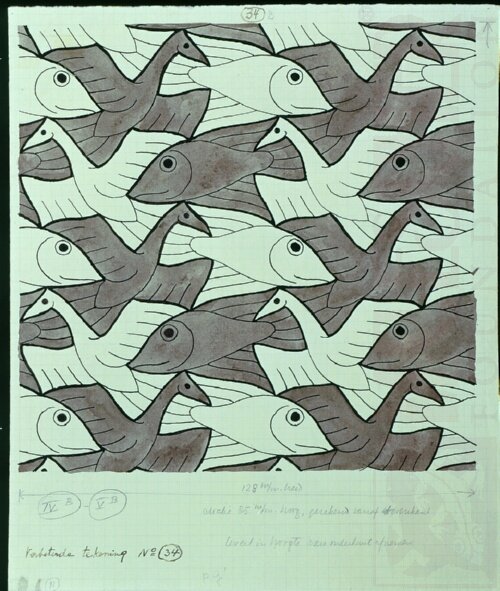

Nullifying the usual distinction between foreground and background leads to images that evoke unconventional viewing experiences. The famous Dutch graphic artist Maurits Cornelis Escher and the Cuban-American abstract painter Carmen Herrera tease our perception by interdigitating two sets of images (Figures 3 and 4). Such juxtaposition forces the viewer’s brain to flip continually between two mutually incompatible interpretations: Is the image black fish and birds with a white background, or white fish and birds with a black background? Is it an orange comb on a green background, or a green comb on an orange background?

Rachel Whiteread

Untitled (Stairs)

2001

© Rachel Whiteread

Unknown

Mountain and Water Ink Painting

Maurits Cornelis Escher

Transitional Systems IV (b) – V (b)

From ‘Symmetry’, 1941

Carmen Herrera

, 1958 Acrylic on cavas,

Whitney Museum of American Art

Leave a Reply